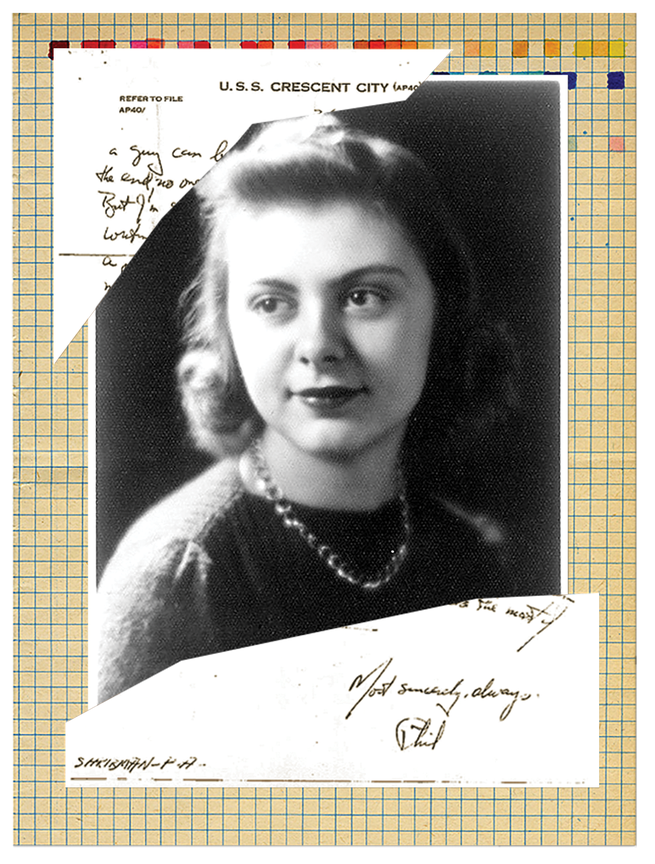

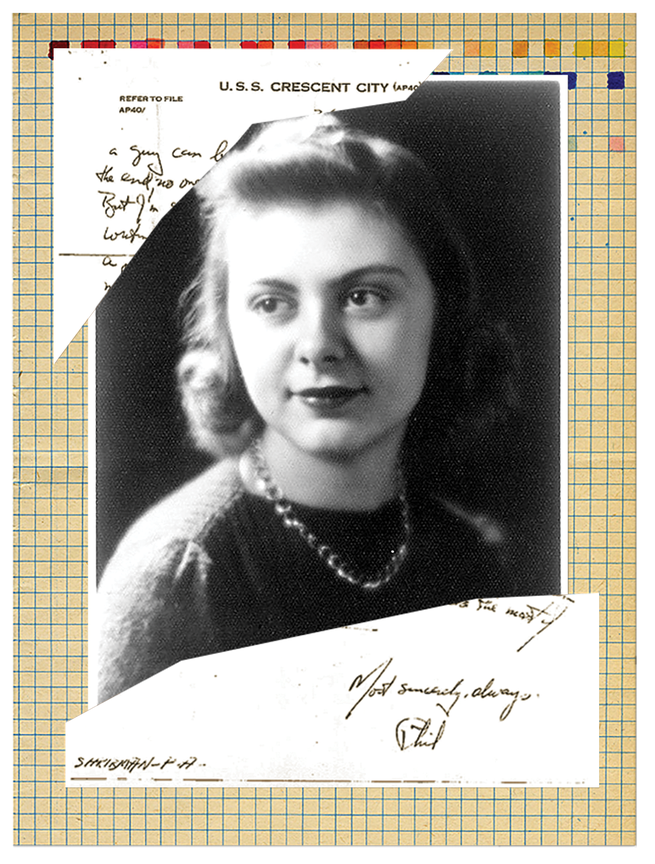

Chugging through Pacific waters in February 1942, the USS Crescent City was ferrying construction equipment and Navy personnel to Pearl Harbor, dispatched there to assist in repairing the severely damaged naval base after the Japanese attack. A young ensign—“real eager to get off that ship and get into action,” in the recollection of an enlisted Navy man who encountered him—sat down and wrote a letter to his younger brother, who one day would be my father.

Philip Alvan Shribman, a recent graduate of Dartmouth and just a month away from his 22nd birthday, was not worldly but understood that he had been thrust into a world conflict that was more than a contest of arms. At stake were the life, customs, and values that he knew. He was a quiet young man, taciturn in the old New England way, but he had much to say in this letter, written from the precipice of battle to a brother on the precipice of adulthood. His scrawl consumed five pages of Navy stationery.

“It’s growing on me with increasing rapidity that you’re about set to go to college,” he wrote to his brother, Dick, then living with my grandparents in Salem, Massachusetts, “and tho I’m one hell of a guy to talk—and tho I hate preaching—let me just write this & we’ll call it quits.”

He acknowledged from the start that “this letter won’t do much good”—a letter that, in the eight decades since it was written, has been read by three generations of my family. In it, Phil Shribman set out the virtues and values of the liberal arts at a time when universities from coast to coast were transitioning into training grounds for America’s armed forces.

“What you’ll learn in college won’t be worth a God-damned,” Phil told Dick. “But you’ll learn a way of life perhaps—a way to get on with people—an appreciation perhaps for just one thing: music, art, a book—all of this is bound to be unconscious learning—it’s part of a liberal education in the broad sense of the term.”

But that wasn’t the end of it, far from it. “If you went to a trade school you’d have one thing you could do & know—& you’d miss the whole world of beauty,” he went on. “In a liberal school you know ‘nothing’—& are ‘fitted for nothing’ when you get out. Yet you’ll have a fortune of broad outlook—of appreciation for people & beauty that money won’t buy—You can always learn to be a mechanic or a pill mixer etc.,” but it’s only when you’re of college age “that you can learn that life has beauty & fineness.” Afterward, it’s all “struggle, war: economic if not actual—Don’t give up the idea & ideals of a liberal school—they’re too precious—too rare—too important.”

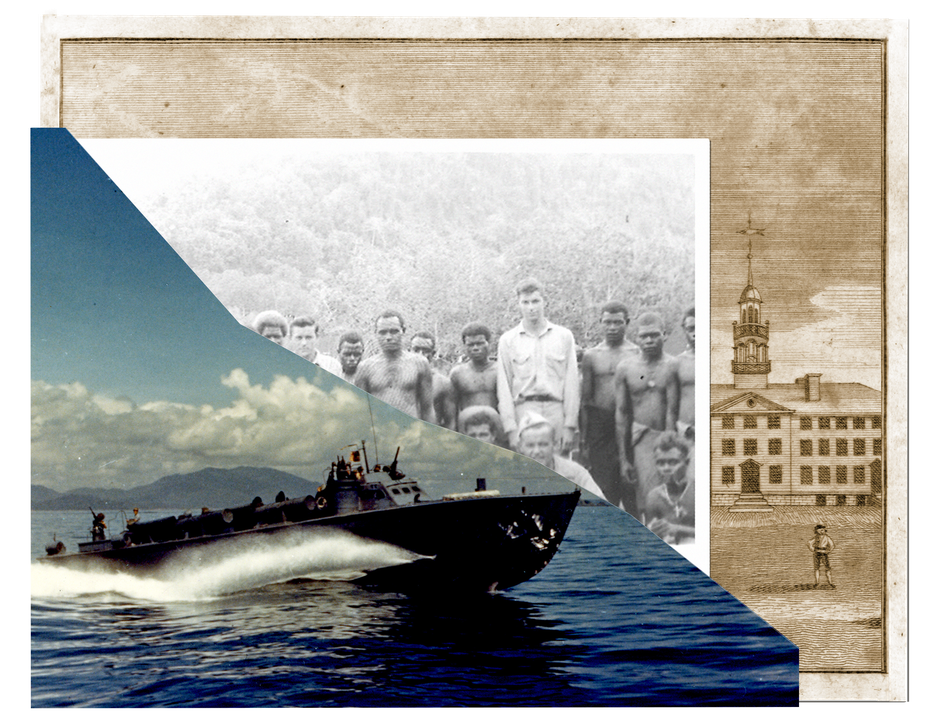

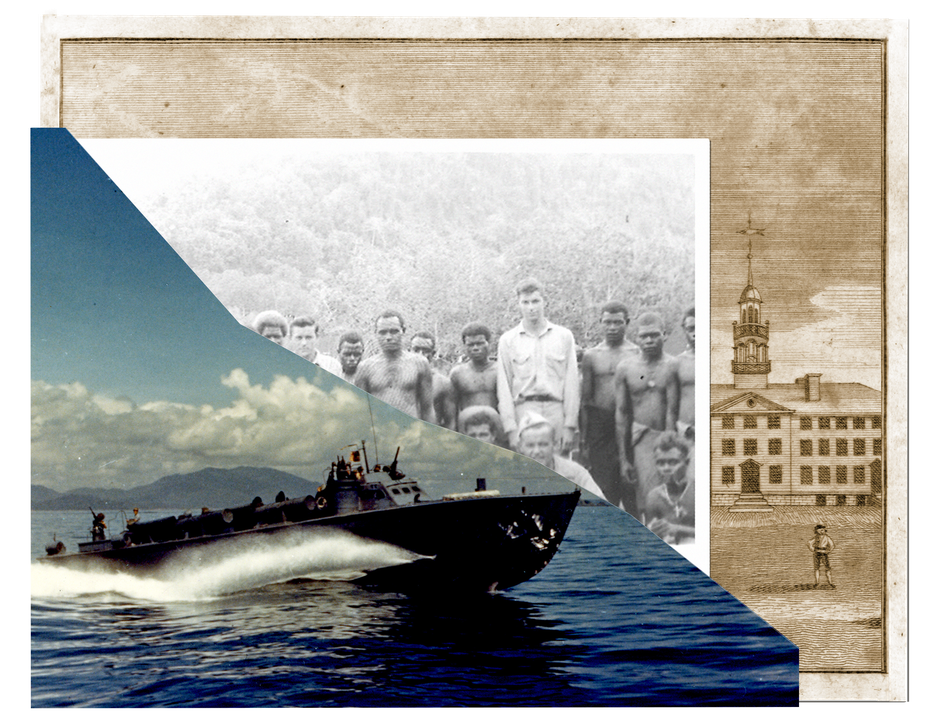

Roughly a month after Phil wrote this letter, the Crescent City saw its first action, off Efate, in New Hebrides, and before long the attack transport set off for Guadalcanal and the initial assault landings in August, on an insect-infected island that was destined to be the site of a brutal six-month jungle struggle in unforgiving heat against determined Japanese fighters.

In September 1942, during the Guadalcanal campaign, Phil wrote another letter, this one to his favorite Dartmouth professor, the sociologist George F. Theriault. “I’ve had lots of time to think out here,” he told Theriault, before adding, “A decent liberal arts education based on the Social Sciences is all a lot of us have left—and more and more becomes the only possible background on which to view all this”—the “all this” referring to the war and what it was about. He told Theriault, who was passionate about preserving the place of literature and the social sciences in Dartmouth’s wartime curriculum, that “no greater mistake could be made than to shunt all the fellows off into ‘war courses’ and neglect the fine, decent, really important things we had a chance to come to know.”

A little more than four months later, Phil was dead. He was on a PT boat by then, and on a night in early February, his boat—PT-111—ran into the searchlight of a Japanese destroyer off the northwest tip of Guadalcanal. Phil was gunned down. But before he died, he had made it clear that the conflict that would claim his life was a struggle for the values he’d learned in college—and, just as important, a struggle for the beauty and fineness he had discovered during his undergraduate years.

“And if at the end of college: if there are still people in the world, around, who’d like to deny experiences like it to others,” he told my father, who would join the Navy before his own college years were completed, “why I hope that you—like me—think it’s all worth while to get in & fight for. One always has to protect the valuable in this world before he can enjoy it.”

Philip Alvan Shribman: the man who died for the liberal arts.

I have been preoccupied with Uncle Phil’s life and death for five decades. The advice he gave to my father from the Pacific has provided the buoys of my own life. The values he prized have become my values. His guidance has shaped the passage of my two daughters through life. And his words take on urgency at a time when liberal education and American democracy are under threat.

During these five decades, I have searched for details of his life, sifting through letters and documents in my father’s file cabinet, and seeking out his classmates and shipmates. In the course of all this, I met James MacPherson, a retired New York City transit worker who encountered Phil on Tulagi, a tiny island in the Solomons that served as home to a squadron of PT boats, and who remembered him as “an affectionate guy, like a Henry Fonda or a Gary Cooper.” At a brewpub in Lawrence, Kansas, I bought lunch for Bertha Lou (Logan) Summers, who likely would have become Phil’s wife if they’d had world enough and time.

I spoke with Robert R. Dockson, later the dean of the business school at the University of Southern California, who was Phil’s roommate on the Crescent City and his tentmate on Tulagi. “We were kids then,” he told me, describing how the two of them would sit on the shore and watch sea battles from afar, all the while complaining about the mud that encircled them. “Those were pretty lonely days.” I corresponded with John C. Everett, who went on to run a textile company and who glimpsed his Dartmouth classmate on the beach at Tulagi through his binoculars. Across 100 yards of water, they waved to each other and, by signal lamp, agreed to meet as soon as possible. Within days, Phil was dead.

And in my very first hours on the Dartmouth campus as a freshman myself—this was 52 years ago—I knocked on the door of GeorgeF. Theriault. It was answered by a lanky man with long gray hair and an emphysemic cough.

“Professor Theriault,” I said. “My name is David Shribman.” He seemed astonished, for how could his former student, who had died 29 years earlier, have a child, the freshman at his door? “No, you could not be.”

He’d had no idea that Phil’s brother had a son. Now the son was standing in the very building, Silsby Hall, where Phil, as an undergraduate, would have taken courses. And so began a remarkable friendship, student and professor, conducted over lunches and dinners, on campus and off, and occasionally at his home, presided over by his wife, Ray Grant Theriault, who told me that one day, on a ski expedition, a student named Phil Shribman, unaware that the woman in the fetching ski outfit was his professor’s wife, had asked her out on a date.

That freshman year, I typed out some of the words from Phil’s letters, fastened them to a piece of cardboard with a squirt of Elmer’s glue, and placed the primitive commemorative plaque on the bulletin board of my room. I kept it in sight until the day I graduated, and I have held on to it ever since.

Phil’s father—my grandfather Max Shribman—was a gentle Russian immigrant in Salem, where the family had washed ashore in 1896. He made a modest, small-city success for himself in real estate and insurance, comfortable enough to purchase the 51 volumes of the Harvard Classics that today sit on my bookshelves. To his sons he passed on his reverence—a pure, innocent love—for the idea of college, for the discipline and the leisure that campus life offers, for the chance to take a quiet breath of fresh air before joining life’s struggles.

In the dozen years I knew my grandfather, I heard him talk of the past only a few times, and each of those reminiscences was about the old days, when his two boys were in college. He loved those years, and I came to love what they meant to him.

The three Dartmouth alumni who interviewed Phil in the winter of 1937 told the admissions office that he was “a good, all around boy, bright, alert and a pleasant personality.” His formal college application was a simple affair. He said he thought about becoming a chemist or a doctor and was interested in current affairs and scientific matters. The form contained this sentence, in his own handwriting: “I am of Hebrew descent.”

The college where he matriculated in the fall of 1937 had no foreign-study programs, no battery of psychologists, no course-evaluation forms—just classrooms with chairs bolted to the floor and, in winter, duckboards fastened to the steps of classroom buildings to fend off the snow and ice. The freshman class had 680 students, a little more than half the current size. Freshmen wore beanies. The year Phil arrived, the football team finished the season with an unbeaten record and was invited to play in the Rose Bowl—but declined the offer because, as President Ernest Martin Hopkins would explain, “if one held to the fundamental philosophy of college men incidentally playing football as against football players incidentally going to college, most of the evils of intercollegiate competition would be avoided.” This was a long time ago.

The theme of the convocation address that Hopkins delivered at the beginning of Phil’s freshman year dealt with the aims of a liberal-arts education; he spoke of “what a liberal college is, what its objectives are, what its ideals are, why its procedures exist.” That day, sitting with his new classmates in Webster Hall, Phil heard Hopkins say that the purpose of a liberal-arts education was not to make someone a better banker or lawyer but rather to foster a “mental enlargement which shall enable you to be a bigger man, wherever the path of life leads you.”

Phil’s own liberal-arts education was demanding, and broad. He took courses in English, French, philosophy, astronomy, economics, psychology, music, and sociology (which eventually became his major). His grades were varied: C’s in freshman English, lots of A’s in sociology, on one occasion a D in French.

He was a member of Pi Lambda Phi, the first fraternity at Dartmouth to accept Jewish students. He was in the debate club. He went to football games, joining the annual migration to the Dartmouth-Harvard contest, which in those days was always played in Boston. He was one of the Dartmouth boys who in October 1940 toppled the wooden goalposts after Earl “Red” Blaik’s last Dartmouth team prevailed against Harvard, 7–6. (Blaik would decamp to West Point the next year, a sign of impending war.) The shard of wood Phil snared after the final whistle now is nailed on my wall, just feet from where I am writing this.

The young man who on his application said he was “of Hebrew descent” took as his honors thesis topic “American anti-Semitism.” The thesis was submitted in January 1941, as the Nazi regime pursued the wholesale destruction of Jewish communities and refined the techniques of murdering Europe’s Jews. Later that year, the aviator Charles Lindbergh would deliver his infamous anti-Semitic speech in Des Moines, Iowa.

The United States issued a draft-registration order in September 1940, only days before classes commenced in Phil’s senior year; a month earlier, Phil had enlisted as an apprentice seaman in the Naval Reserve. President Hopkins had assured the Army and Navy that Dartmouth would be responsive to any needs the two services expressed. In the spring of 1941, a student wrote an open letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt (“Now we have waited long enough …”) that was published on the front page of the campus newspaper. It was read into the Congressional Record. The United States wasn’t yet at war, but the campus almost was.

Dartmouth’s Class Day, which takes place in a sylvan amphitheater just before commencement, ordinarily is a joyous occasion. Class Day 1941 was unlike any before or since. Charles B. McLane—the captain of the ski team, who became a member of the fabled 10th Mountain Division before returning to Dartmouth as a professor—delivered the Address to the College (an assignment that 35 years later would come to me). He said that “the strength and assurance of democracy” lies in his classmates’ “being able to believe in and being willing to fight for” the “uncomplicated things we know and believe in today.” That weekend, Hopkins delivered his commencement address:

Men of 1941, sons of this fostering mother of the north-country which we call Dartmouth, it is your generation that will determine, not in middle life but tomorrow, next year, or at the latest within a few brief years, whether the preconceptions you impose upon facts, the faults you visualize in democracy, and the ruthlessness you ignore in totalitarianism shall paralyze your will to defend the one and to defeat the other or whether with eyes wide open to reality, you accept freedom as an obligation as well as a privilege and accept the role for yourself of defenders of the faith.

Shortly after the class of 1941 dispersed, Hopkins would write that “the liberal arts college now has a clear duty to do all it can to aid in national defense; at the same time it would be derelict in its most important obligation if it lost sight of the purposes for which it primarily exists and the coming generation’s need for college-trained men.”

By the time Phil died, a Naval Training School had opened on campus with a staff of about 100, and headquarters in College Hall. Alumni Gymnasium became the site of instruction in seamanship, ordnance, and navigation. Dartmouth eventually added to its curriculum such courses as nautical astronomy, naval history and elementary strategy, and naval organization.

It was that precarious balance between preparing men for war and preserving the liberal arts that Phil sought to defend.

Death came to my uncle with suddenness but not with surprise. His Dartmouth contemporary John Manley once told me that Phil had had a premonition that he would die in the conflict.

After graduation, Phil was assigned to the Crescent City and appointed lieutenant (junior grade). “I can see him today—tall & slender, with reddish brown hair and some freckles, a smile always, irreverent behavior,” his shipmate William Trippet, who would become a real-estate agent in Sacramento, California, wrote me 30 years ago.

During the Guadalcanal campaign, the Crescent City made 14 trips bringing men and supplies to the island. Phil wrote to his parents in September, a month into the fighting, to assure them that he was doing fine. He was, of course, thinner, and yet he had grown. He recalled that he was reminded continually of a letter printed in the newspaper during the last war from a serviceman to his family; it had been sitting around somewhere at home, back in Salem. “Little then,” he wrote, “did I think I would ever sit down in the midst of a war and … put down a little of what a person thinks.” His own letter was spare, meant only as a “personal sort of thing, like I was back in our living room telling it to you.” He spoke of being in close quarters for 60 days; of seeing men die; of settling down someday with the right girl. Here was a boy who had grown up.

“They say that the Navy, esp. in wartime, either makes a man or shows that no man will be made,” he wrote. “As to what the outcome on my part will be I will have to leave that to someone else and until it’s over.”

On January 5, 1943, he was transferred to the PT-boat squadron, an assignment he had wanted. PT boats have an audacious aura because of the experience of John F. Kennedy, who commanded one—PT-109. They were perhaps the flimsiest element of the American naval force—usually a mere 80 feet long, outfitted with machine guns and four 21-inch-diameter torpedoes, and capable of zipping through the sea at more than 40 knots. The Navy’s approximately 600 PT boats were designed to be the seaborne equivalent of guerrilla warriors, able to ambush and scoot away quickly. But they were no match for what became known as the Tokyo Express, the Japanese warships that bore down on Guadalcanal.

On the island of Tulagi, an American staging area for the Guadalcanal battle, Phil lived in a bamboo-and-banana-leaf shack measuring about 12 by 15 feet and sitting some four feet off the ground. “Sweat rolls freely in January,” he reported in a letter to Theriault. Among his neighbors in the shack were a nest of hornets, one of spiders, and two of ants—“companionable,” he wrote, “so we let them be.” Little else is known of his life on Tulagi in those last few months. A single photograph survives, showing Phil standing tall among a group of Solomon Islanders.

On February 1, 1943, an Allied coast watcher reported seeing as many as 20 Japanese destroyers in the Slot, the name given to the maritime route used by the Japanese for the resupply of Guadalcanal. That night, American PT boats set out as part of a larger effort to intercept the destroyers. PT-111 was among them. John Clagett, the commander, steered his craft away from the base. The boat was jarred by an exploding bomb nearby. Eventually he found a target, a Japanese destroyer moving on a southeasterly course, three miles east of Cape Esperance. PT-111 fired all four of its torpedoes from close quarters and then maneuvered away. Whether the torpedoes did any damage is unknown. But shellfire from a destroyer hit Clagett’s boat, which exploded in flames. Ten members of the 12-man crew survived, some rescued the next morning after nine hours in the water. One member, legs broken, likely was taken by sharks. Phil himself seems to have been killed outright in the attack. PT-111 sank into Iron Bottom Sound.

Back in Salem, a telegram arrived at 5 Savoy Road. “The Navy Department deeply regrets to inform you that your son Lieutenant Junior Grade Philip Alvan Shribman United States Naval Reserve is missing following action in the performance of his duty in the service of his country.”

I can only imagine the scene when this message arrived. Did the Western Union man drive down the street, stop at the white house on the left, climb the concrete stairs, and deliver the telegram? Did someone from the Navy visit? My father was away, at Dartmouth. I know only this: That moment was the hinge of my grandparents’ lives.

A few blocks away from their house, an obelisk erected to honor the 2,105 veterans from St. Joseph’s Parish who served in the two world wars stands on a median between Washington and Lafayette Streets. When I was a cub reporter for the Salem Evening News, I would pass the monument and see the inscription on one side: TIME WILL NOT DIM. I think about that legend constantly. Time did not dim the force of that loss.

Senator Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. sent a note saluting Phil for having “gone to join the heroes who have built America.” That may have been a form letter, but the note from Phil’s Crescent City shipmate Zalmon Garfield, later the executive assistant to Milton Shapp, Pennsylvania’s first Jewish governor, was not. Garfield wrote on behalf of his shipmates about the respect and admiration they had for Phil:

Some of these men are ignorant, some of them callous; en masse, however, their judgment of their officers is uncannily unerring … It is a strange day in which we live, watching the gods toss their finest works into a chasm of their own building. We can only wonder, mourn briefly and work very hard to replace the loss.

Republican Representative George J. Bates of Salem was visiting injured American combatants in West Coast hospitals shortly after the delivery of that fateful telegram and, in a remarkable coincidence, encountered John Clagett, Phil’s commander on PT-111, recuperating from his injuries. “Tell Philip’s father that his son was one of the most courageous men I have ever seen in action,” the commander told the congressman.

With the news of Phil’s death, Bertha Lou Logan entered my grandparents’ lives. Her father, a football coach and high-school principal, had raised her alone after her mother died in childbirth. She had met Phil at the Grand Canyon in July 1939. He was traveling with Dartmouth classmates; she was there with family. As the two parties moved west, Phil and Bertha Lou left notes for each other at post offices. Eventually Bertha Lou took a waitressing job at Loch Lyme Lodge, near Dartmouth. Later, in Chicago, when Phil was in midshipmen’s school, he and Bertha Lou would walk by the lake. She was the girl he wanted. He was the boy soon to be rendered unattainable.

After Phil died, Bertha Lou wrote Max and Anna Shribman, whom she had never met. She took the train to Salem, and my dad picked her up at the station. She lived in my grandparents’ house for some while, the three of them united in a triangle of grief. “It took me a long time to get over him,” Bertha Lou told me when I met her in Kansas decades later.

In 1958, John Clagett wrote a novel titled The Slot about life aboard a PT boat during World War II. He was by then an English professor at Middlebury College. “These days are dead,” he wrote in an author’s note. “We hated them then, we would not have them come again; but after fifteen years may we not look back at them for a few hours and say—Those were days that counted in our lives.” And, in a different way, in mine.

For three-quarters of a century, historians have sorted through the “war aims” of Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini, Hideki Tojo, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, and Joseph Stalin. In college and graduate school, and in a lifetime of reading, I have examined much of that scholarship. But for Americans, the war was also about more than carefully stated aims—it was about far simpler things, really, but no less grand. Texaco had it right in a 1942 magazine advertisement that depicted a man carrying Army gear and saying, “I’m fighting for my right to boo the Dodgers.” Phil might have added that it was also about the right to feel joy pulling down a goalpost in a dreaded rival’s home stadium; the right to struggle with explaining in what respects Stendhal, Balzac, and Flaubert were realists; the right to get a C in English and a D in French.

“Look around you—keep your eyes open—try to see what’s what—hold onto the things that you know to be right,” Phil wrote to my father in what could be a user’s guide to the liberal arts. “They’ll shake your faith in a lot of the things you now think are right—That’s good—& part of education—but look around & try to make up your own ideas on life & its values.”

In 1947, five years after that letter was written, my grandfather sent some money to Dartmouth to establish a scholarship in his son’s name—specifically, to support a student from the Salem area. The scholarship continues, and every year the family receives a letter about the person awarded the scholarship. I have a pile of them.

One of the recipients of that scholarship was Paul Andrews. He took the classic liberal-arts route that Phil would have endorsed—psychology, meteorology, music—and today is a school superintendent in central Oregon. Another was Matthew Kimble—history, religion, biology—who would chair the psychology department at Middlebury. A third is Christine Finn—drama, economics, organic chemistry. She is now a psychiatry professor at Dartmouth’s medical school. Another is Jeffrey Coots—astronomy, mythology, American literature—who specializes in public health and safety at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice. You could say that Phil won World War II after all.

I have been delving into Uncle Phil’s life for years. Some of the very sentences in this account I wrote more than half a century ago, the product of an 18-year-old’s effort to repay a debt to an uncle he never knew. Those sentences stood up well. So has my faith. And so, too, has my belief that, as Uncle Phil put it from the Pacific War 80 years ago, “you know actually it’s the things I (and everyone else) always took for granted that are the things the country is now fighting to keep—and it’s going to be hard to do.”

This article appears in the May 2024 print edition with the headline “The Man Who Died for the Liberal Arts.”